Life: The Dynamics of Misery

Olga Mexina

Oct 29, 2012

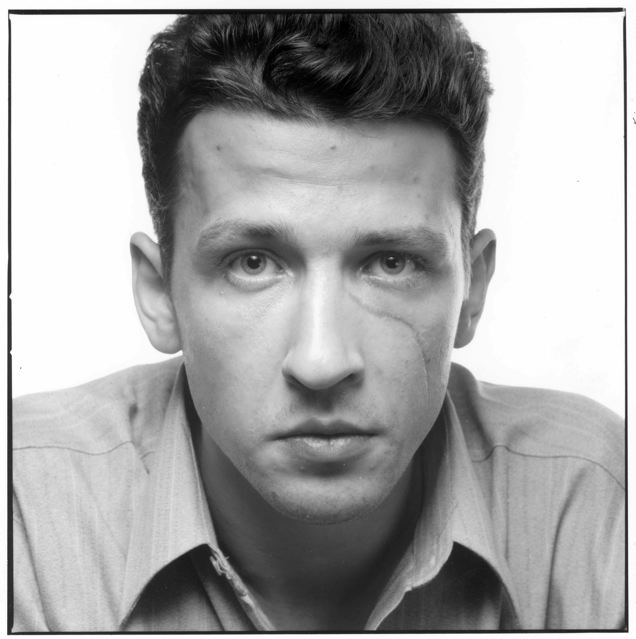

• Last will V. S. Let's agree to this: when I die, you will put a cross on my grave. Let it be like all other crosses, but we, my friend, we will know, it is--just a signature. As on paper the illiterate leaves his mark, I want to leave a cross in this world. I want to leave a cross. At odds I was with life's grammar. I read my fate, but understood nothing. I was accustomed only to blows, the blows, from which the words like teeth fall out of the mouth. And smell like blood. --Boris Ryzhy (November 1993) I often find myself frustrated by the socially and culturally imposed importance of 'having fun', 'enjoying' yourself, being 'happy', thinking 'positive thoughts.' Sometimes I just want to shout, I am not sad, I am not depressed, I am just human. Sometimes I want to do this in the middle of a seminar or while talking to somebody. And, yes, sometimes I want to die, but honestly, I think that's normal. Like certain people I know think it is suspicious when somebody never drinks (what are you hiding from us), I find myself not being able to trust people who are always chipper (you are lying to me, I know). The essence of human condition is life, i.e. we are constantly dying, and as they say, that's okay. Recently I've been translating the contemporary poet Boris Ryzhy, whom I've been obsessed with for some time. His poetry exhibits the signs of absorption and respect for the poetic canon, but like a true poet he has his own voice, language, and syntax, which reflect the reality and specificity of his own time. His poetic world explicitly exposes the human condition through juxtapositions of very tangible objects with less material ones. His world is transparently honest, if not always completely sober, and truth, as many of us know, hurts. The speaker of Ryzhy's poems is keenly aware of life's transience, always seeing each event, every emotion in the context of binary oppositions: life/death, love/parting, belonging/alienation, and, ultimately, human strength/human weakness. The speaker understands and continuously reiterates the idea that one always has a bit of the other. Ryzhy's poetry, while fairly rhetorical, taps into and inhibits a world of ultimate humanity, where emotion is logic. • Like ears, the brims of the soaked hat gently swayed--a sad elephant, playing the trumpet, looked at the waves. And the seagulls landed on the last table. These just drank, and those--shouted, and the streetlight burned, not a streetlight--a little streetlight. He played on the pierce, black, like death-- he blew the moon like a balloon. And it seemed--there was a certain feeling-- when he leaves that place--the sea will disappear, the little steamer, seagulls--it will be so sad, and you'll take a sip of grief, my friend, not beer. That's why I pressed, and shoved the bills-- for him to play, as long as our hearts burned: For that shithead, for this bitch, actually, my gentle, for me. (November 1994) In an interview, Ryzhy once said that a poet needs no special tragedy in his life, that being a poet is tragic enough. His biography is a testament to that; his first love led to his only marriage producing a son. He said that he likes people and life to be 'natural' as opposed to being 'overthought' or 'intellectualized.' Ryzhy's poetry while seemingly very 'natural' is nevertheless meticulously constructed; there is nothing redundant. He channels the dynamics of misery, which is life. • There is no money, no wine½ --Adamovitch --Come, my friend, through the empty street, where streetlights hang like tangerines, and there is snow, simple January snow, and stores are closed forever. Advertisement glitter, store windows, rain-pipes, ditches. --So sad, my friend, so terrible, so literal. And you? What do you expect from life? --Sadness, my friend, the beautiful--is sad. It's all true, and we walk past the black walls. --Tell me, what will happen to us tomorrow? And the hideous eternal mannequin watches us with beautiful eyes. --What does he know? That this world is cruel? That it's dreadful? That roses in the store windows are dead? --That happiness exists, but cold tears, my god, --alas--obscured it from you. January, 1995 Yes, beautiful things are sad. That's how we can appreciate and experience the ultimate beauty: when it is pushed to the foreground by sadness. The sadness that tells you, this beauty is slowly dying, dissipating. And that is truly beautiful. That's why poetry exists outside political correctness and literary theory, outside feminist theory, outside queer theory--in fact, poetry exists outside language itself. • I will never write how much I love Russia. --Roman Tyagunov Like a kind of--let's say--Goyan freak confess his love to a beauty, covering his mouth with his hand, cannot, only sweat chills his forehead, until my hands and legs shook I could not express this feeling-- because God was beside you then. Now crouching on the dying grass, holding my palm to my disheveled head, I think about our frightening bond. And I say: I love you, yes and yes, to the very tears, and I am not ashamed anymore, for my ugliness, because you are walking towards pain and darkness, a muddy bottom, where eyes have a residue, like that wine½ Or I am walking, though--it's all the same. (March 1995)

Comments (0)

Add a Comment